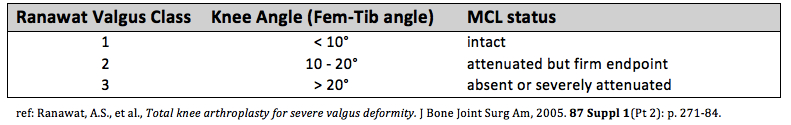

Only 10% of knee deformities that require TKA are done for the valgus knee. The Ranawat classification [1] uses 3 grades to describe valgus deformity severity. Grade I is <10° valgus deformity (normal valgus angle is ~ 6°), correctable alignment with stress, and intact MCL and this type accounts for >80% of all valgus knees. Grade II is an angle 10° - 20° degrees, MCL is attenuated but a firm endpoint, and this type accounts for 15% of valgus knees. Grade III is a valgus angle >20° and absent or severely attenuated MCL. This grading scale helps to determine the type of implants and correction that is required.

Soft tissue considerations.

If the MCL is intact, then a primary TKA poly insert can be used. If the MCL is elongated, a constrained poly may be necessary to give sufficient coronal stability. Literature shows there is a risk of recurrent valgus deformity after primary TKA when the MCL is deficient and primary insert is used (even when satisfactory ligament balancing occurs at the time of surgery) [2]. The use of constrained poly effective prevents this recurrence [3]. A constrained insert absorbs more of the joint reactive forces, and the next question is whether stems are necessary to increase the surface area of the bone-implant interface to absorb these greater forces [4]. Some argue that an elongated MCL is still functional and a constrained insert without stems is not at increased risk for loosening. If the MCL is completely absent, a hinge prosthesis should be considered as excessive stress to a constrained insert may cause significant wear and early loosening and post fracture.

MCL attenuation also adds significant challenge to gap balancing. In a varus knee, the tight medial structures are released to match the normal or slight attenuated lateral side (the point is that the lateral side is rarely significantly loose). In the valgus knee however, the MCL can be significantly pathologic, and by releasing the lateral structures to match the enlongated MCL, you can significant increase the size of the gap (because you are using a very pathologic structure as your target), and you may even lengthen the operative leg, require a large poly, and put the peroneal nerve at risk for traction injury.

There is debate about the order of soft tissue releases to achieve a balanced gap. Releases should be performed with the knee in extension and the balance should be rechecked after every release. Ranawat recommends “inside-out” technique of pie-crusting the IT band, then the LCL with a no. 15 blade, and making effort to preserve the popliteus. [1] The peroneal nerve is at risk between IT band and Popliteus at the level of the tibial cut. Studies show that LCL release provides the most correction, and some recommend releasing first in cases of severe valgus deformity [5] [2].

Bone considerations.

The valgus knee is uniquely different from the varus knee because bone loss occurs on the lateral femur (in contrast to vaurs knee that shows anterior-medial tibial bone loss. The entire Lateral Femoral Condyle can be significantly hypoplastic (posterior and distal femoral condyles). This is important to identify if the surgeon is measuring femoral rotation by posterior referencing, which typically add 3° to compensate for the difference in sizes between the medial and lateral femoral condyle. In the case of a hypoplastic LFC, the posterior referencing system may need to dial in 5° or more to prevent internal rotation of the femoral component. Additionally, if there is more than 5 mm of deficient bone on the posterior or distal femoral cut, augments should be considered because a cement mantle this large will lead to early loosening. It is important not to chase a large bone defect. If the distal femoral cut does not touch the lateral femur, do not resect additional distal femur because this will raise the joint line, causing patella baja. Similarly, if there is tibial bone loss, measure 4-6 mm off the medial side (non-affected side) to determine the depth of the cut, attempting to cut distal to the defect often removes excessive bone (“apb”: always preserve bone!). The distal femoral cut is often made at only 3° as opposed to the standard 5 – 7° to avoid undercorrection of the deformity.

REFERENCES

1. Ranawat, A.S., et al., Total knee arthroplasty for severe valgus deformity. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2005. 87 Suppl 1(Pt 2): p. 271-84.

2. Favorito, P.J., W.M. Mihalko, and K.A. Krackow, Total knee arthroplasty in the valgus knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg, 2002. 10(1): p. 16-24.

3. Easley, M.E., et al., Primary constrained condylar knee arthroplasty for the arthritic valgus knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2000(380): p. 58-64.

4. Anderson, J.A., et al., Primary constrained condylar knee arthroplasty without stem extensions for the valgus knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2006. 442: p. 199-203.

5. Krackow, K.A. and W.M. Mihalko, Flexion-extension joint gap changes after lateral structure release for valgus deformity correction in total knee arthroplasty: a cadaveric study. J Arthroplasty, 1999. 14(8): p. 994-1004.