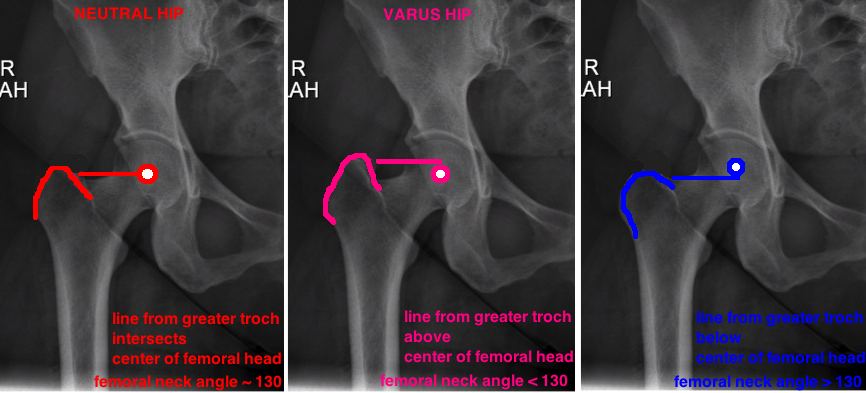

Average adult femoral neck shaft angle is 135, but this is only an average. The neck angle can be measured by placing one line down the center of the femoral shaft and a second line down the center of the femoral neck.

A high neck angle is a Valgus Hip, a low neck angle is a Varus hip. The amount of varus or valgus can also be measured by placing a point at the center of the femoral head (representing the hip center) and extending a line out to the tip of the greater trochanter (see picture). In a "normal hip" the center of the femoral head should be at the same level as the tip of the greater trochanter, while a Varus Hip the center of the femoral head lies below the tip of the greater troch, and a Valgus Hip the center of the femoral head lies above the tip of the greater troch.

Importantly the neck angle affects forces across the hip because it changes the tension of the abductor mechanism. A valgus hip results in improved mechanical advantage to the abductor while a varus hip generates greater forces across the hip center.

Most femoral components of a total hip replacement rely on bony ingrowth for long term fixation. Bony ingrowth occurs during the first 6 weeks after a THA, and similar to the fracture healing, it requires micromotion < 50 nm for ingrowth to occur, otherwise, fibrous ingrowth occurs and there is increased risk for persistent motion, early loosening and symptoms of thigh pain. Thus, for proper ingrowth to occur, the press-fit must be obtained at the time of surgery - the implant must fill the proximal canal and place enough hoop stress on the rim of cortical bone to prevent micromotion. Both axial (the stem doesnt sink into the femoral canal) and torsional (the stem cannot rotate within the canal) stability are required for initial stem fixation.

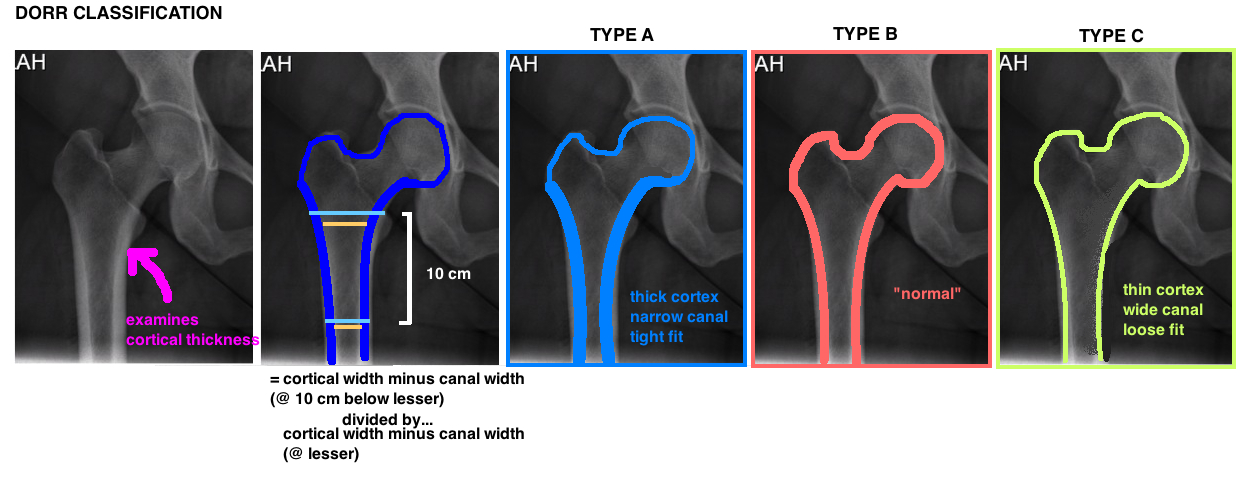

The best press-fit occurs when the implant design matches the native femoral canal. The challenge is the variability of proximal femur anatomy within the population. The Dorr Classification is the most commonly used classification system for describing the relationship between the proximal femoral anatomy and the emoral diaphysis, otherwise known as the Canal-Flare Index. This can help with surgical planning to select a stem that will maximize the ability of achieving a press-fit during surgery. In general, as we get older, we lose bone stock, and the metaphyseal region of the proximal femoral canal becomes more and more capacious. This has implications on the ability to use a non-cemented/press-fit stem.

More specifically the Dorr Classification describes the relationship of the diameter of the proximal femoral canal relative to the femoral diaphysis. Its calculated by measuring the ratio between the canal width at lesser trochanter and the canal width 10 cm below the lesser troch. It actually measures the relative thickness of the cortex by calculating the difference between the full diameter of the bone compared to the diameter of the canal alone (see diagram).

TYPE A femurs have a thick cortex and narrow canal (referred to as a “champagne flute”) and commonly found in men and younger patients. It permits good cementless fixation with low risk of fracture, however, selecting the proper implant can be challenging given the metaphyseal-diaphyseal mismatch. A single wedge stem design is often used.

TYPE B femurs demonstrate some medial and posterior cortex bone loss, and therefore a wider canal, and are an intermediary between Type A and C. Most femurs are a Type B.

TYPE C femurs demonstrate significant cortical bone loss particularly in the medial and posterior cortex with a capacious canal (referred to as a “stovepipe”), and is common in postmenopausal women and should warn surgeons of concern for cementless fixation particularly difficulty in controlling rotational motion, and increased risk for intraoperative fracture.